Volunteers across Malaysia are leveraging technology to further drive the production of personal protective equipment (PPE) for frontliners, and ensure that the protective gear goes to the right people as quickly as possible.

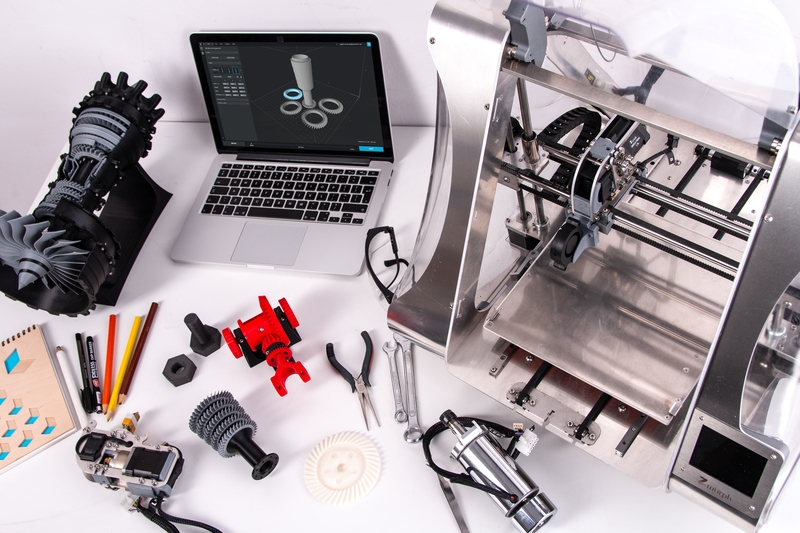

One such initiative, the Open Source Community Fight Against COVID-19, is a group one a massive social media platform comprised of tech enthusiasts who are using 3D printers, laser cutters and plastic injection moulding machines to produce safety gear.

Around 200 active volunteers have armed themselves with more than 500 3D printers, some of which were loaned to them by businesses that wanted to help.

One of its coordinators stated that the effort was kickstarted by the 3D printing community, but others with injection moulding machines have joined the cause, tremendously increasing the production speed.

The 3D printers take about 40 minutes to make one unit of PPE, needing more than a week to produce more than 20,000 units.

In comparison, the eight injection moulding facilities can produce more than 22,000 units in just a single day!

News spread like wildfire and soon varsities started joining in to help contribute where they could, he said.

Varsities that have joined the fray include Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM) and Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka (Utem).

While the volunteers can mass-produce basic types of PPE, most are unable to make complex devices like ventilators, powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs) or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines.

This is due to them not having access to CNC (Computer Numerical Control) routers and other industrial machines.

Quality control was also a challenge but was mitigated by following standardised designs adapted from the international open-source community.

The group also streamlined the production processes, drawing up guidelines not only for producing PPE safely and hygienically but also organising and distributing them. The group had help from Sabah, Sarawak and the east coast.

However, the group soon realised that other large collectives were also working along the same lines, so the volunteers used various online groups to share their work and communicate with each other’s team leader.

Making it happen

Seeing that the non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and volunteer groups had the same goals but were not necessarily on the same page, one volunteer felt the solution required something more elegant than just online groups and Google sheets.

She noted that it was quite disempowering to read how dire things are and not being able to do anything.

“When volunteering, I look for areas where I can be most helpful, but also I try not to replicate others’ work – if an initiative is already running that addresses a gap, I’d love to collaborate,” she said.

So she chose Airtable, a Cloud collaboration service that combines the features of a spreadsheet with a database, allowing everyone to view which hospitals require supplies and if the requests are being fulfilled.

She started by talking to the team members, analysing their work processes and finding out the info they required to work efficiently.

It is useful for data entry. Various volunteers just input the info into a form and the data is transformed into a spreadsheet. And it’s also great for giving the public an overview, as the data is updated dynamically.

There was also a need to address a second concern – verification – as the volunteers realised that some people were requesting for face masks and hand sanitisers to resell at inflated prices.

To combat profiteering, the groups not only started verifying requests, ensuring that they came from hospitals, but also started partnering with logistics companies so the supplies would go directly to the medical institutions.

Beyond the peninsula

While much of the news about the pandemic appears to be centred around the Klang Valley, other states are also facing the widespread virus and have formed their volunteer groups.

Compared to the Klang Valley, these groups are even more decentralised, having to be based out of cities and townships that are geographically remote from one another.

The Head of the Sarawak Multimedia Authority (SMA) Digital Village head stated that decentralisation has not been much of an issue, as most volunteers are not working as one organisation but a movement comprising many subgroups and individuals with a similar purpose.

He described the overall initiative as a loose collaboration of various groups across the state, made up of about a thousand volunteers collectively.

The SMA coordinated with universities and STEM trainers and even the Sarawak state library to kick off 3D printing, while social enterprise Tanoti Crafts and residents of the Puncak Borneo Prison in Kuching helped sew hospital coveralls.

Together they produced PPE like face shields with 3D printers and even assembled some with sponges, plastics and staplers, as well as disposable hoods and booties sewn out of sterilisation wrap.

The movement started in late March 2020, at about the same time as other groups, and they started coordinating and dividing up tasks as they got to know each other.

They also received aid from groups in the peninsula – some sent filaments for 3D printing.

The groups are very informal; teams are just focused on looking out for each other and getting through this. And though the groups are mostly self-contained, there’s a spirit of volunteerism among them.

Meanwhile, a collective in Sabah made up of groups and institutions volunteering 3D printers and skills, including the Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Sabah State Library, Malaysian Dental Association (MDA) and Petrosains Maker Studio.

Its community leaders said that though they coordinate with each other, everyone is free to work towards their own goals.

MDA not only helped in collecting and delivering the PPE to hospitals and medical centres but even sanitised the items and liaised with the Sabah health department.

They established that for Kota Kinabalu, while volunteers everywhere else in Sabah are advised to liaise with clinics or hospitals in their locality.